Introduction

All businesses, including insurance companies, have a philosophy, or an ethical position, whether to comply or not comply with external requirements. This article analyzes the processes of a compliance program in the context of the property and casualty insurance industry of the United States, from the perspective that a company’s philosophy is to comply with external requirements (laws), and that the company has an established and effective compliance program. The processes within a compliance program are discussed in more detail below and are offered as a model of best practices.

A company’s philosophy is often stated in a corporate ethics policy which provides a general framework for the entire company. The effectiveness of a company’s compliance program is largely dependent upon the given company’s philosophy. A philosophy that is supportive of compliant practices gives these companies a competitive and profitability advantage over companies that do not have a supportive policy or an ineffective compliance program.

A compliance program, like any other program, is administered through its processes. Beyond a supportive philosophy, the effectiveness of a compliance program is dependent upon processes within the program.

To ensure understanding, the terms listed below are used as follows:

- Compliance: the act or process of conforming to a desire, demand, or proposal or to coercion, a disposition to yield to others1

- Laws: a rule of conduct or action prescribed or formally recognized as binding or enforced by a controlling authority2 (includes laws, statutes, regulations, administrative codes, court rulings, and hearing decisions as issued by a governmental agency with jurisdictional authority)

- Program: a plan or system under which action may be taken toward a goal3

- Process: a series of actions or operations conducing to an end4

The Processes of a Compliance Program

The goal of a company’s compliance program is to assist the company in meeting its financial goals by focusing on at least three separate processes.

- Pre-compliance monitoring

- Compliance implementation

- Post-compliance validation

Pre-Compliance Monitoring

The pre-compliance monitoring process focuses on three areas: the monitoring of governmental agencies for proposed new laws or changes to current laws; analyzing these proposals to determine likely affects on the business; and possible attempts to influence the proposal to a more favorable outcome. This process necessarily concentrates on the three branches of the government.

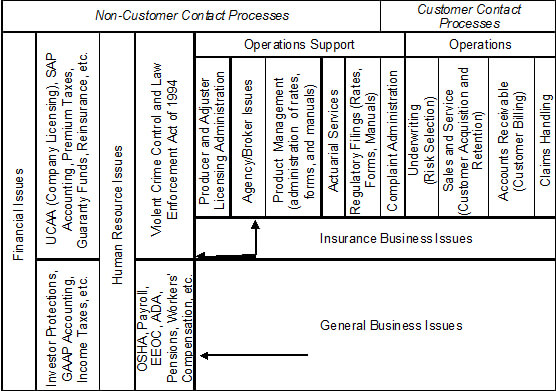

Besides governmental agencies there are other external sources that may impose limits on businesses. Additionally, a business may limit its actions though policies the company adopts. Table 1 summarizes this information.

|

Source

|

Form of Requirement

|

| Government – Executive branch, through functional regulators. State regulators for the business of insurance are known as a Department of Insurance (or something similar). States sometimes also have other regulatory bodies for specific insurance lines of business, such as workers’ compensation. |

Regulations and Administrative Codes, Hearing Decisions |

| Government – Legislature |

Statutes |

| Government – Judiciary |

Court Rulings |

| Trade Association, Business Partner, Vendor, or Other Companies |

Contracts |

| The Company Itself |

Internal Policies |

Table 1 – Sources of Limitations upon Business Processes

Laws are enacted by and enforced through the authority of the government; contracts by the signing parties; and policies by companies. Since laws are enforceable by the government, laws are complied with. Companies voluntarily agree to sign contracts and thus voluntarily agree to fulfill their obligations under the contract and expect all other parties to the contract to do the same. Companies and employees agree to a mutual exchange of payment for work. By accepting payment, the employee agrees to the terms of employment, which includes agreeing to follow company policies, and companies expect their employees to follow company policies. With the compelling forces behind contracts and company policies being self-imposed (voluntary), the proper term to describe abiding with contracts and policies is adherence, not compliance.

Each of the sources of requirements upon businesses is explored next.

Regulatory Agencies. State governments are the primary regulators of the insurance industry in the United States, based upon U.S. federal law (the McCarran-Ferguson Act of 1945), which stipulates:

No Act of [the U.S.] Congress shall be construed to invalidate, impair, or supersede any law enacted by any State for the purpose of regulating the business of insurance, or which imposes a fee or tax upon such business, unless such Act specifically relates to the business of insurance: Provided, That after June 30, 1948, the Act of July 2, 1890, as amended, known as the Sherman Act, and the Act of October 15, 1914, as amended, known as the Clayton Act, and the Act of September 26, 1914, known as the Federal Trade Commission Act, as amended (15 U.S.C. 41 et seq.), shall be applicable to the business of insurance to the extent that such business is not regulated by State Law.5

Although state insurance departments are the primary regulators, many other state and federal agencies also affect the industry. For example, a state’s Department of Labor has regulations that affect all businesses that hire employees. Specific to insurance, regulations from a state’s Department of Motor Vehicles address topics such as financial responsibility and auto insurance identification cards. The Federal Trade Commission, through the Fair Credit Reporting Act, imposes requirements upon companies that use consumer reports to underwrite or rate business. To remain compliant, companies should monitor for new and changes in existing laws from the federal government and all state agencies.

A regulatory agency’s authority is derived from a legislative statute, which often empowers the appropriate regulator to publish regulations to implement and administer the statute’s requirements. Some jurisdictions grant regulators the authority to conduct administrative hearings, which enable regulators to issue binding decisions without a formal court proceeding.

Legislative Actions. Some laws apply to all but exempted businesses. Examples include income taxes, employee safety and payroll laws, and medical information privacy. All companies are subject to income taxes unless exempted under the law. All businesses that employ more than a specified number of employees must abide by employee safety and payroll laws. Before an individual’s health information is obtained, medical care providers and the requesting party must abide by the privacy requirements of the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA).

Some laws apply only to a specific activity, such as the business of insurance. Although most state statutes that affect an insurance company’s operations are grouped together in a state’s insurance code, some statutes that affect operational activities appear outside of the insurance code. Insurers writing homeowners insurance need to know about statutes often categorized as family law for risks related to a daycare business in the home. Insurers writing auto insurance need to review the motor vehicle or traffic code for laws about driver’s licenses and other topics. A comprehensive review of all of the various codes is needed to identify all statues that affect the business of insurance.

In addition to legislation, another method of laws being enacted is ballot propositions which are approved in elections. Twenty-seven states allow propositions to be placed on ballots in a variety of forms, including through the collection of voters’ signatures or directly by an elected legislature.6 The effect of ballot propositions that receive a majority popular vote is the same as a legislative bill that becomes law.

Judicial Decisions. Court decisions, called either case law or common law, may involve an individual or class, be from any level of government (city, county, state, or federal), and may or may not be specific to insurance. A decision may be narrowly construed to the case decided or it may strike entirely or a portion of or redefine a statute, regulation, contract, or a previous court decision. Insurance companies need to monitor case law because a violation of court rulings would result in non-compliance.

Non-Governmental Limitations on the Processes of Companies. Contracts into which a company voluntarily enters with a trade association, partner, vendor, or other businesses often require the company to agree to certain limitations or provide information on the insurer’s activities. For example, a contract may specify that the products or services may only be used for lawful purposes, or have restrictions on whether data obtained through the particular business relationship may be shared outside that relationship.

A contract may also require the company to provide data on its activities. A company may choose to be a member of a trade association or rating organization. One of the requirements of being a member may include providing data on the company’s business activities, such as premium volumes by line of business or claim indemnification payments.

Lastly, a company may limit its activities through its own policies. For example, many states permit insurers to use consumer credit information as a rating factor, yet a given insurer’s policy may be to not use credit information. Thus, insurers may refrain from exercising legally permitted rights.

Upon identification of all of the sources of requirements, a compliance program would establish a process to monitor for changed or new requirements from these sources. This is discussed below.

Initiation of the Pre-Compliance Monitoring Process

The pre-compliance monitoring process is initiated when an external requirement from a governmental authority is proposed. Before laws are enacted, companies regularly analyze proposed laws to determine if their passage would require the company to change any of its business processes. The pre-compliance monitoring process consists of at least three activities:

- Monitoring the sources of law changes

- Analysis of the proposed changes and the expected affects on the relevant business process.

- Possible attempts to influence a governmental official to pass or not pass laws that are deemed beneficial or harmful to the company or expression of support for those proposals that are viewed as being favorable.

Employees responsible for the company’s compliance implementation process, in coordination with the business area or areas that would be affected should a legal requirement change, typically handle impact analyses. The analysis is then communicated to the company’s staff that is registered as lobbyists of government officials. Lobbying attempts occur in at least four different ways.

- A legislator is asked to support or withdraw a bill or amend it to be favorable or have no effect.

- The governor is asked to sign or veto a bill.

- A regulator is asked to introduce or withdraw a proposed regulation or amend it to be favorable or have no affect.

- Businesses directly communicate with customers or request communication through a trade organization or lobbyist. The purpose of the communication is to educate customers as to the positive or negative affects on customers and the particular business of the proposed law and to request the customers to notify their elected officials of their support for or against the proposed law.

Companies may also attempt to influence the outcome of a pending court case. Although the company is not a party in the lawsuit, if it has sufficient interest in the outcome, the company may attempt to persuade the court to decide the case in accordance with its interests. This attempt is accomplished through an amicus curiae (friend of the court) filing.

While employees supporting the compliance implementation process identify suggestions to document a company’s stance on a proposed change, lobbying, developing customer correspondence, and filing legal petitions require specialized skills. The first three lobbying methods usually are handled by the company’s staff with governmental affairs responsibilities or a contracted lobbying firm. The fourth lobbying method would probably include these same areas along with the business department for customer communications, and staff or retained counsel, with the expertise to petition a court, would handle the last lobbying method.

The pre-compliance monitoring process assists a company to meet its financial goals by identifying legal requirements and attempts to mitigate the extent of these requirements. A company that does not monitor and analyze proposed new laws and changes to existing laws faces unknown legal risks.7 The consequences of these unknown risks range from a nominal fine to a threat to the company’s survival. A company that does not engage in lobbying activities may be limiting its opportunities to eliminate or constrain the affect of proposals, which if enacted, would be an expense to the company.

Once the compliance monitoring process is completed, the result will either be that the company is now subject to an altered or new requirement. As this occurs, the next process within the compliance program begins.

Compliance Implementation

The goal of the compliance implementation process is to ensure that a company analyzes all laws which may affect its business activities and to make changes to become or remain compliant with those laws. The compliance implementation process begins when a new law or changes to an existing law are enacted, which requires monitoring of all of the governmental agencies identified in the previous section. A compliance implementation process and the staff that support it should bridge the company’s legal counsel with the company’s business functions. Once aware of a new or changed law, employees responsible for this process in a company react to the new law and proactively execute this process.

The steps in the compliance implementation process are to:

- Identify all of the requirements contained in the changed or new law.8

- Understand the requirements. If the requirements are not understood, an attorney who specializes in the particular section of law should be consulted.

- Understand the business process that is affected. This is accomplished by meeting with the functional area responsible for the process.

- Determine what changes, if any, need to be made to the business process in consultation with the functional area and other necessary areas (computer systems, etc.).

- Document that the appropriate changes were made by the business area affected by the law.

Companies may choose to monitor for changes to laws by subscribing to a service or joining a trade association that provides notices of new statutes and regulations. Another monitoring method is to routinely review state government legislative and regulatory websites for information on new statutes and regulations.

Case law, administrative law, and alternative dispute resolution methods such as binding arbitration, each of which issue binding decisions that address a specific situation, also need to be monitored. Changes to a business process may be required to comply with a judicial or administrative ruling or arbitration decision. If so, the compliance process steps should be followed to ensure the business process is appropriately changed to be compliant.

In addition to responsibilities for monitoring changes in existing laws or new laws, a compliance implementation process should be used to evaluate changes to processes initiated by management proposals. This evaluation should help ensure that all business processes are compliant and that those who administer the compliance implementation process are aware of all business processes. The first two steps in the compliance implementation process are modified during a review of management proposals to:

- Find out what the requirements are as contained in the management decision.

- Understand the requirements. If the requirements are not understood, additional details should be sought from management. As needed, an attorney should be consulted.

A compliance implementation process that is consistently followed will ensure that compliance is systemically integrated into all business processes. This proactive control increases the likelihood that the company will be consistently successful and fulfills the goal of the compliance implementation process.

After the implementation process is completed, there may be interest in validating that the process was properly completed. The final process to be completed is post-compliance validation.

Post-Compliance Validation Process

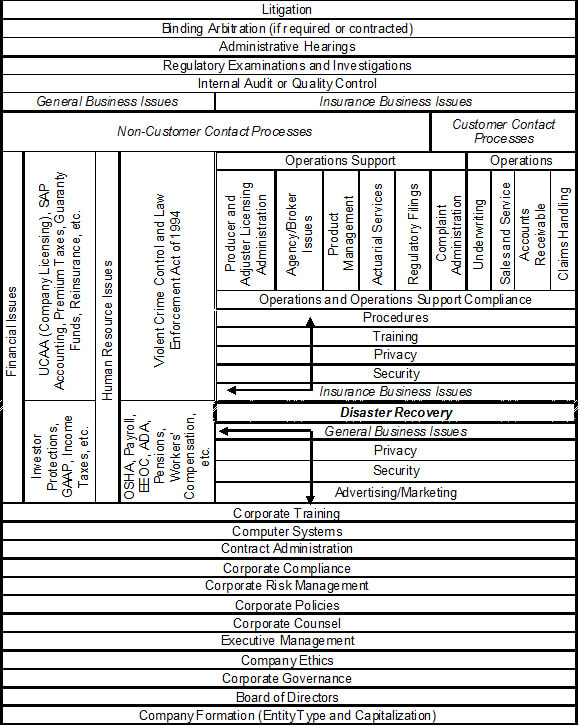

Post-compliance validation of the effectiveness of a compliance implementation process is conducted either internally or externally. Validation is determined internally by an audit or externally by a regulatory examination, a regulatory or judicial hearing, or through arbitration. From the perspective of the company, the goal of post-compliance validation exercises is to protect the company by determining whether the compliance implementation process was accurately completed. From the perspective of an external examiner, the goal is protect insurance consumers by determining if the company was compliant or non-compliant.

Companies utilize internal auditing as a “safety net for compliance with rules, regulations, and overall best business practices.”9 State regulators have statutory responsibility and authority to conduct examinations and hearings to protect consumers.10 Judicial hearings and arbitration are legal proceedings that are granted respectively through lawsuits or contractual requirements.

An audit or exam that determines the company did not properly comply with the requirements of the laws under review subjects the company to:

- take corrective actions (possibly including premium refunds or additional claim settlements);

- assess the reason or reasons why the compliance implementation process failed; and

- regulatory fines.

However, should the determination be that the company did properly comply with legal requirements, it will validate that the compliance implementation process was successful. In so doing, it also confirms that the process assisted the company to meet its financial goals by avoiding the consequences of not complying as listed above.

Separate Skills Required for Each Process

The pre-compliance monitoring and compliance implementation processes each require skills unique to that process. As noted, the lobbying skill of pre-compliance is different from the skills required with implementing changes to be compliant. For each process to be effective, and therefore a competitive advantage, a company should select staff to administer each process of its compliance program with employees who have the required skills for the particular compliance process. Similarly, the internal process of conducting audits or the internal process of supporting external examiners requires different skills than those necessary for pre-compliance monitoring and compliance implementation. For a company to administer these processes as “other duties as assigned” is to fail to see the unique nature of each process.

Compliance Case Study

The case study below emphasizes the iterative nature of handling changes to existing laws and new laws and points out the differences of compliance and other business processes. Activities are identified as occurring externally or internally with respect to the insurer and the entity taking the action.

The study entails what appears to be a relatively simple proposal: to reduce the initial underwriting period, during which an insurer is permitted to cancel a policy with few restrictions, from 60 days to 45 days. Such a change would require that the underwriting of newly accepted risks and determination to continue or cancel the policies in a shorter timeframe.

This fictional jurisdiction requires each insurer to file its underwriting manual and agree to arbitration for unresolved disputes between the insurer and insured; permits consumers to sue insurers; and the insurance department has the authority to conduct examinations and administrative hearings. This apparently minor change to one of a fictional jurisdiction’s underwriting laws also illustrates the complexity of compliance within the business of insurance.

I. Pre-Compliance (External): State Legislature

A legislative bill is introduced to reduce the initial underwriting period from 60 days to 45 days.

II. Pre-Compliance (Internal): Governmental Affairs, Compliance, and Underwriting Departments

The insurance company’s governmental affairs department notifies the compliance department of the bill. After analysis of all expected changes necessary at a high level, the compliance department coordinates a response with underwriting and responds to governmental affairs. Governmental affairs may take no action or work with a lobbyist or trade association, directly lobby legislators or the governor, or testify at a legislative hearing to ensure that the company’s position on the bill is known.

III. Pre-Compliance (External): Legislature and Governor

The legislature passes the bill. If the governor signs the bill, or if the governor vetoes the bill but the legislature overrides the veto, the bill becomes a public act.

IV. Compliance Implementation (Internal): Compliance, Underwriting, Procedures, Training, Computer Systems, and Regulatory Filings Departments

The compliance department becomes aware of the public act and follows its process to:

- Identify all of the requirements contained in the changed or new law.

- Understand the requirements. If the requirements are not understood, an attorney who specializes in the particular section of law should be consulted.

- Understand the business process that is affected. This is accomplished by meeting with the functional area responsible for the process.

- Determine what changes, if any, need to be made to the business process in consultation with the functional area and other necessary areas (support, computer systems, etc.).

- Document that the appropriate changes were made by the functional area.

The simple change of reducing the initial underwriting period from 60 to 45 days would be easily identified and understood by the compliance department. An attorney’s assistance is not needed to clarify the change to the law, but staff counsel would likely be notified to ensure awareness of the change. The compliance employee would then discuss the issue with an underwriting department employee to determine the scope of the changes. After this consultation, a detailed account of all affected processes would be made.

Compliance with this change in law requires:

- Creation of a new mandatory amendatory endorsement that changes the section of the insurance policy which discusses the number of days notice needed to cancel a policy. The endorsement needs to be filed with the state by the company’s regulatory filing department;

- Amendment and filing of the company’s underwriting manual by the company’s regulatory filing department;

- Modification of the procedures, forms and correspondence used to send notice of cancellation to consumers, training, and computer systems used by underwriters;

- Communication of the change to all underwriters; and

- Communication of the change to claims staff, so claim handlers are aware of the new amendatory endorsement as it affects policy effective dates.

The compliance specialist would document that the changes made to remain compliant took place by the effective date of the law, provided there was sufficient lead time to accomplish the necessary changes before the law’s effective date and in consideration of when regulatory approvals to use the amendatory endorsement and revised underwriting manual are received.

With both simple and complex laws, an insurance company must review all affected processes to ensure it is meeting its compliance obligations. Thus, a company that has already established a systemic compliance process is in a better position to effectively comply with a law requiring complex changes than a company that does not have a systemic compliance process.

V. Post-Compliance (Internal): Auditing Department

The company’s internal auditing or quality assurance/control department conducts an audit to determine if:

- Regulatory approval to use the amendatory endorsement and revised underwriting manual were received;

- The amendatory endorsement was attached to policies after the regulatory approval date;

- All initial underwriting cancellations are sent within the first 45 days of the policy;

- Any claims were improperly denied based on an improper cancellation date, and;

- If any of these items was not properly handled, to determine what corrective actions are necessary.

VI. Post-Compliance (External): State Insurance Regulator, Arbitration, and Judiciary, and Post-Compliance (Internal): Various Departments

- Customer Complaints: Customers write to the insurance regulator and assert that cancellation notices are not valid because they were sent after the first 45 days from the policy issue date. The regulator sends the complaint to the insurance company’s consumer affairs department, which would coordinate with the underwriting department to provide a response.

- Market Regulation: The state department of insurance conducts a market conduct examination. With respect to this topic, the examination would review the same points which the company’s internal audit reviewed. The business unit within the company that coordinates regulatory examinations is involved and would coordinate with the regulatory filing, underwriting and claim departments.

- Administrative Hearing: The state department of insurance holds an administrative hearing following consumer complaints alleging that cancellations are taking place after the first 45 days, to determine if the allegations are accurate. The company would have representation at the hearing, perhaps a government affairs specialist, attorney, or underwriter.

- Arbitration: An individual consumer who believes that the initial underwriting period cancellation was invalid requests that the company submit to arbitration. The company would likely be represented by an attorney at the arbitration proceedings.

- Litigation: An individual consumer, or a class of consumers, sues the insurance company for sending initial underwriting period cancellation notices after the initial underwriting period. The company would be represented either by staff or retained counsel.

Both simple and complex legal requirements must be properly understood, coordinated, and implemented to ensure compliance. A compliance process that is proactive and systemic permits a company to be proactive and systemic in handling allegations of non-compliance.

Summary

Every business, as part of the larger society, is subject to government oversight. Businesses have an interest in proposed law changes that may alter their business processes (pre-compliance monitoring), in following laws (compliance implementation), and in confirming compliance (post-compliance validation) and therefore form a compliance program to administer these processes. A pre-compliance monitoring process must monitor all government sources for proposals to change current law or for new laws to ensure risk exposures to the company do not remain unidentified. With the enactment of a new law or a change to an existing law, a compliance implementation process reacts to the law to proactively change its business processes. Post-compliance validation of a company’s compliance processes may be conducted by the company, a regulator, or through arbitration or a judicial proceeding.

The primary goal of any company is to be profitable. One way for a company to meet its financial goals is to support compliance as a separate business function that links the company’s other business programs to the company’s legal counsel and governmental affairs lobbyists. In so doing, companies establish a competitive advantage over companies that either do not support compliance activities, do not treat compliance as a separate business function, or have an ineffective compliance program or processes.

References

4. Merriam-Webster, Inc., Merriam-Webster Online, Dictionary definition of the noun “process.” [

http://www.m-w.com/dictionary/process], accessed April 2, 2007.

5. Office of the Law Revision Counsel, U.S. House of Representatives. “The McCarran-Ferguson Act, Section 1012 (b)., accessed March 6, 2006.

6. Initiative and Referendum Institute, “States with Direct (DA) and Indirect (IDA) Initiative Amendments; Direct (DS) and Indirect (IDS) Initiative Statutes and Popular (PR) Referendum.”, accessed March 20, 2007.

7. According to Wolters Kluwer Financial Services, more than 10,000 new federal and state laws, regulations, and administrative orders were proposed from January – July 2009, representing a 70 percent increase for the same period in 2008. This demonstrates the exposure that is faced by not monitoring. Quoted in National Underwriter Online News Service, by Daniel Hays, “Insurance Legislation Surges This Year In Congress, Legislatures”, September 17, 2009. [

http://www.property-casualty.com/News/2009/9/Pages/Insurance-Legislation-Surges-This-Year–In-Congress-Legislatures.aspx], site accessed January 5, 2010.

8. Through the identification of changes that would have to occur if a proposed law is passed, a pre-compliance monitoring process that involves those employees involved in the compliance implementation process simplifies the compliance implementation process.

Initiative and Referendum Institute, “States with Direct (DA) and Indirect (IDA) Initiative Amendments; Direct (DS) and Indirect (IDS) Initiative Statutes and Popular (PR) Referendum”,.

The Institute of Internal Auditors, “Frequently Asked Questions – Internal Auditing”, [http://www.theiia.org/about-the-profession/internal-audit-faqs/?i=1078].

The Maven’s Word of the Day, “roger wilco”, [http://www.randomhouse.com/wotd/index.pperl?date=19970207].

Merriam-Webster, Inc., Merriam-Webster Online, Dictionary definitions of the words compliance, complying, law, process, and program, [http://m-w.com/dictionary/compliance], [http://www.m-w.com/dictionary/complying], [http://m-w.com/dictionary/law], [http://www.m-w.com/dictionary/process], [http://www.m-w.com/dictionary/program].

National Underwriter, “Insurance Legislation Surges This Year In Congress, Legislatures”, [http://www.property-casualty.com/News/2009/9/Pages/Insurance-Legislation-Surges-This-Year–In-Congress-Legislatures.aspx].

New York Insurance Law Chapter 28, Section 304 and Section 309, [http://codes.lp.findlaw.com/nycode/ISC/3/304 and http://codes.lp.findlaw.com/nycode/ISC/3/309].

Office of the Law Revision Counsel, U.S. House of Representatives. “The McCarran-Ferguson Act, Section 1012 (b), [http://uscode.house.gov/uscode-cgi/fastweb.exe?getdoc+uscview+t13t16+1469+4++%28mccarran%2].

United States Army, Fort Belvoir, Virginia, History of the term WILCO, [http://www.afms1.belvoir.army.mil/dictionary/w_terms.htm].

Joseph L. Wiest, CPCU, ARC, ACP, is a corporate compliance director of market conduct with a top ten P&C insurance group. He is a graduate of the University of Nebraska, having earned a B.S. in business administration. Since 1984, he has been employed in the insurance industry, working 20 years for a major personal lines direct writer, holding positions in customer service, line underwriting, staff underwriting, and compliance. He also served as the compliance officer of a nonstandard auto carrier for two years. He has earned a business ethics certificate from Colorado State University in addition to nine other professional insurance designations.

“Do what you love and you will never work a day in your life.”

“Do what you love and you will never work a day in your life.”

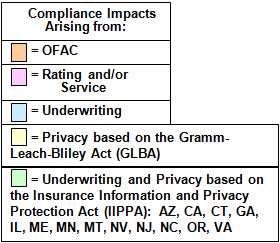

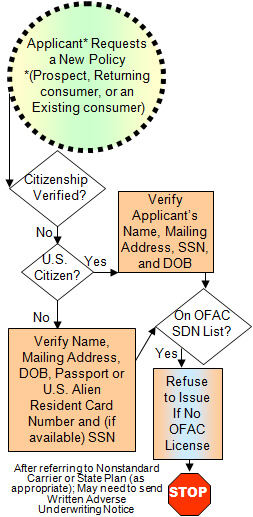

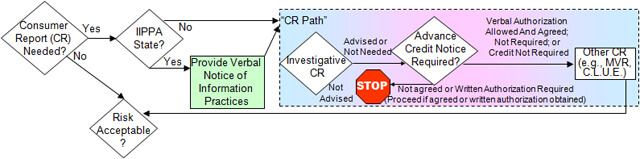

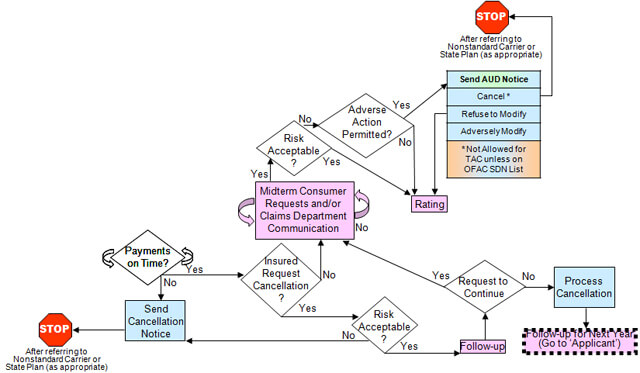

How these categories of laws affect underwriting is presented in a time sequence begining with a new applicant requesting a policy and ending with the policy being renewed. All of the individual sequences are part of the underwriting process and are used as to graphically display the entire process with the color coding above. The first category to discuss is economic sanctions.

How these categories of laws affect underwriting is presented in a time sequence begining with a new applicant requesting a policy and ending with the policy being renewed. All of the individual sequences are part of the underwriting process and are used as to graphically display the entire process with the color coding above. The first category to discuss is economic sanctions. Consumer Report Compliance

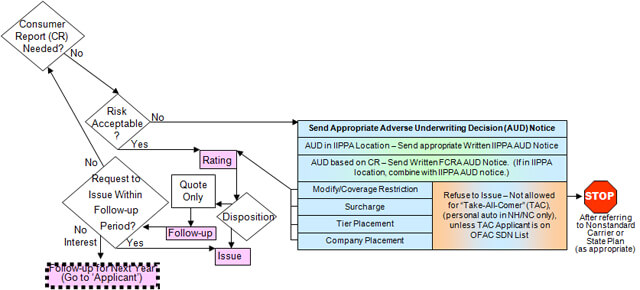

Consumer Report Compliance The next phase of the underwriting process is determining if the risk is acceptable.

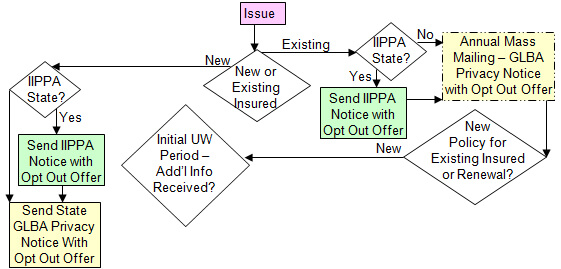

The next phase of the underwriting process is determining if the risk is acceptable. If a request is made to issue the policy, then determining which written privacy notice or notices must be sent needs to be determined next.

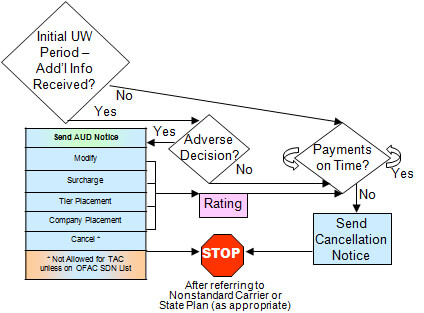

If a request is made to issue the policy, then determining which written privacy notice or notices must be sent needs to be determined next. Initial Underwriting Period Risk Acceptability and Adverse Underwriting Decision Compliance

Initial Underwriting Period Risk Acceptability and Adverse Underwriting Decision Compliance The next process, which is also continuous, encompasses insured’s requests to cancel the policy, making decisions regarding consumer requests for policy changes and/or communication from the company’s Claims Department that may be made during the life of the policy.

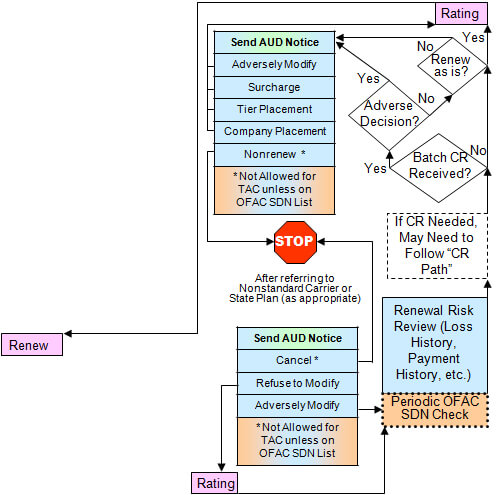

The next process, which is also continuous, encompasses insured’s requests to cancel the policy, making decisions regarding consumer requests for policy changes and/or communication from the company’s Claims Department that may be made during the life of the policy. Periodic OFAC Compliance, Renewal Risk Acceptability and Adverse Underwriting Decision Compliance

Periodic OFAC Compliance, Renewal Risk Acceptability and Adverse Underwriting Decision Compliance The final process is determining which privacy notices to send with the offer to renew the policy.

The final process is determining which privacy notices to send with the offer to renew the policy.