INTRODUCTION

In regards to “compliance”, the word can be used to mean anything to do with laws, working with regulators, or even auditing. To assure fluency and comprehension, “compliance” is used to mean abiding with the requirements of “laws”, i.e., constitutions, laws, statutes, regulations, court rulings, etc., promulgated by a governmental body with appropriate jurisdictional authority.

- Federal economic sanctions

- Money, or financial matters

- Employees, or human resources issues

- The business of insurance, or operations

- Activities that support insurance operations

A discussion of compliance with federal economic sanctions and notable laws specific to insurance follows. (The Appendix has a listing of laws that generally apply to financial, human resources, and business activities of all industries.)

FEDERAL ECONOMIC SANCTIONS COMPLIANCE

Federal economic sanctions apply to all United States citizens and businesses, arching over other compliance requirements. The regulations enforced by the United States Treasury’s Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) prohibit insurers from “engaging in [financial] transactions not licensed by OFAC that in any way involve”[3] individuals named on federal terrorist or narcotics trafficker lists or in certain countries[4] unless OFAC has pre-approved the transaction by issuance of a license. This applies to insurance companies, brokers, business partners, and employees, and includes transactions such as collecting premium to issue a policy[5],[6] and paying a claim[7],[8]. Although OFAC has published risk matrices as guidance for financial services, charities, and securities firms to assess their risks in relation to compliance with the economic sanctions administered by OFAC,[9] no risk matrix has been published for the insurance industry.[10]

The next category of laws deals with financial issues affecting property and casualty insurance companies. These laws are typically administered by a corporate finance department.

INSURANCE FINANCE COMPLIANCE

Insurance companies are expected to comply with laws addressing these financial matters.

- Company Formation and Capitalization

- Domiciliary jurisdiction – compliance with the business laws of the jurisdiction where the company is domiciled, filings with Secretary of State and capitalization requirements of insurance regulatory authority.

- National Association of Insurance Commissioner’s (NAIC) Uniform Certificate of Authority Application (UCAA) – required filing of financial documents with a state’s insurance regulator to obtain a certificate of authority to sell insurance in a state.

- Accounting Practices

- SAP (Statutory Accounting Principles)

- Solvency

- Reinsurance

- Guaranty Funds

- Internal controls over financial reporting, including revisions to the Annual Financial Reporting Model Regulation (the Model Audit Rule)[11]

- Reinsurance

- Guaranty Funds

- Premium Taxes (state, county, municipality)

- Producer commission payments

- Environmental Compliance – Insurers with direct written premium over $300 million must complete the Insurer Climate Risk Disclosure Survey to provide regulators and insurance consumers a method to “assess insurers’ risk assessment and management efforts” regarding climate change risks, focusing on insurer solvency and insurance availability and affordability.[12] Twenty-one states require insurers to complete the survey.[13]

The next category addressed is compliance with laws regarding employers and employees. These laws are typically administered by a staffing or human resources department.

INSURANCE HUMAN RESOURCES (HR) COMPLIANCE

Most of the laws that address how companies and employees interact apply to all industries. There is a short list of laws that specifically apply to insurance companies.

- Payroll Administration (requires interaction with Finance)

- Commission payments – to company employees who are licensed and paid as producers

- Employee Ethics

- Violent Crime Control and Enforcement Act of 1994 (18 USC §§ 1033-34)

The discussion continues with a focus on compliance with laws specifically addressing the business of insurance.

INSURANCE OPERATIONS COMPLIANCE

Some laws, especially at the state level, affect only the business of insurance (operations) or only a specific type of insurance, such as auto or homeowners. The major topics are:

- Advertising/Marketing (Sales and Service)

- Unfair Trade Practices Acts

- Producer advertising materials

- Risk Selection (Underwriting)

- Declination

- Rescission

- Terminations

- Initial Underwriting Period

- Midterm Cancellation

- Nonrenewal

- Partial (policy modification to remove a coverage or impose a higher deductible)

- Consumer Reports Used by Insurers

- FCRA (Fair Credit Reporting Act, as amended by the FACT Act of 2003)

- Permissible use

- Disposal

- Adverse use

- Various laws restricting or prohibiting the use of credit information, including “freezes”

- Acquisition and Retention (Sales and Service)

- Assigned Risk (automobile) and Residual Markets (property Market Assistance Plan [MAP], Fair Access to Insurance Requirements [FAIR] program, and Wind, Beach and Coastal Plans)

- Rating – charging the same rate for the same risk, prohibited rating factors

- Accounts Receivable (Customer Accounting)

- Billing

- Payment Posting

- Refunds

- Claims Handling

- Unfair Claims Practices Acts

- Adjuster Licensing

- Continuing Education

- Notice to insurance regulators following “for cause” termination

- Privacy – affects all operations processes (Most notably, state insurance privacy laws passed in response to the federal Gramm-Leach Bliley Act and the NAIC Model Insurance Information and Privacy Protection Act)

- Notice of Information Practices

- Opt Out provisions

- Use and display of customers’ Social Security Numbers

- Security

- Ensuring information collected from customers is secure from unauthorized access

- Notifying customers in the event of a breach of security

- Business Continuation/Disaster Recovery

These laws affect the major processes of insurance operations, which are:

- Underwriting – risk acceptability selection and routine monitoring for continued acceptability

- Sales and Service – acquisition of new business and retention of insureds

- Billing – customer accounting or accounts receivable

- Claims handling – settling claims based upon contractual language and facts of the loss

OPERATIONS SUPPORT PROCESSES

To support the major processes of insurance operations, insurers engage in at least six additional distinct processes. None of these involve routine customer contact except complaint administration.

- A company is responsible to validate licenses and continuing education, to appoint, and to notify states when appointments are terminated for employees who are producers and adjusters.

- For companies that use agents or brokers to sell and service its insurance products, the insurer needs to administer contracts, commission payments, and business relationships with the agents and brokers.

- Product development and management works closely with actuarial services and with regulatory filings and handles:

- The development of new policies, coverages, and endorsements and the maintenance of existing products

- Ensuring that wording used by contracts, forms, endorsements, and general correspondence for use with customers meets all legal and business requirements

- Production and maintenance of rate and form manuals for the use of employees who deal with customers

- Release of new or revised rates, forms, etc., into production after all necessary filings have been approved

Companies sometimes establish one business area for the development of new products and another for the maintenance of existing products.

- Actuarial services supports product management by developing adequate and competitive rates for underwriting risks accepted by the company. A company’s claims department relies on actuaries to develop loss reserves for probable future liabilities related to unpaid and incurred but not reported claims.

- Various laws require companies to file rates, forms, manuals, or data in response to new laws or changes in laws, when the company initiates changes to its products, or at the request of an insurance regulator. The regulatory filings department administers this process. Filings must be made in specific formats and provide details about issues such as the purpose of the filing, premium affects upon insureds, and an actuarial memorandum that supports any rate changes. Filing of data to fulfill regulator requests requires validation of the data accuracy to ensure the regulator is provided with reliable information. Various regulatory agencies at both the state- and federal-level require insurers to file periodic routine reports, such as a state law requiring insurers to notify the state department of transportation of vehicles no longer insured by the company or federal law requiring liability, no-fault, and workers’ compensation insurers to report payments made to Medicare beneficiaries to the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (an agency of the Health and Human Services Department).[14] Many states also require ad hoc reports, such as monthly updates regarding the numbers of claims presented and closed after a catastrophe.

- Consumer protection laws require companies to respond to and keep record of complaints. Regulators thoroughly review complaint-tracking reports and/or directly review complaints when conducting market analysis and during market conduct examinations.

The next section addresses how a property and casualty insurer coordinates compliance with all of these laws by the establishment of various processes.

THE PROCESSES OF A PROPERTY AND CASUALTY INSURANCE COMPANY

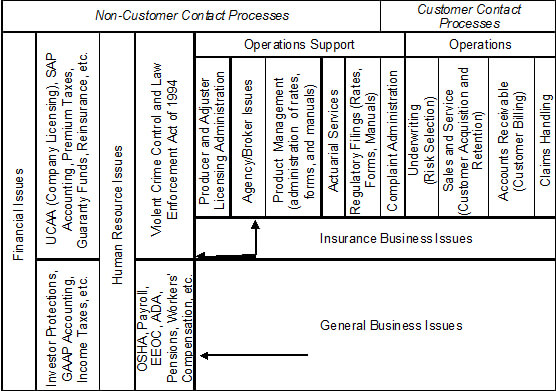

VERTICAL PROCESSES. Project management refers to a process that drives the flow of knowledge as a “vertical process.”[15] All of the insurance processes discussed above are vertical processes. How they fit together is demonstrated in Table 1.

Table 1 – Vertical Processes – Insurance Company

The laws affecting finance and HR issues to a large extent determine the processes within a company’s finance and HR departments. Accordingly, the compliance process is often integrated within the finance and HR processes. The finance and HR processes generally do not involve contact with customers.

Insurance operation processes provide service to insurance customers by directly interacting with customers. The compliance process is either integrated in each of the operations and operations support processes or it may be centralized within a compliance department. If centralized, the employees supporting the operations and operations support processes are able to fully focus on and maximize their skills directly related to their respective specialties.

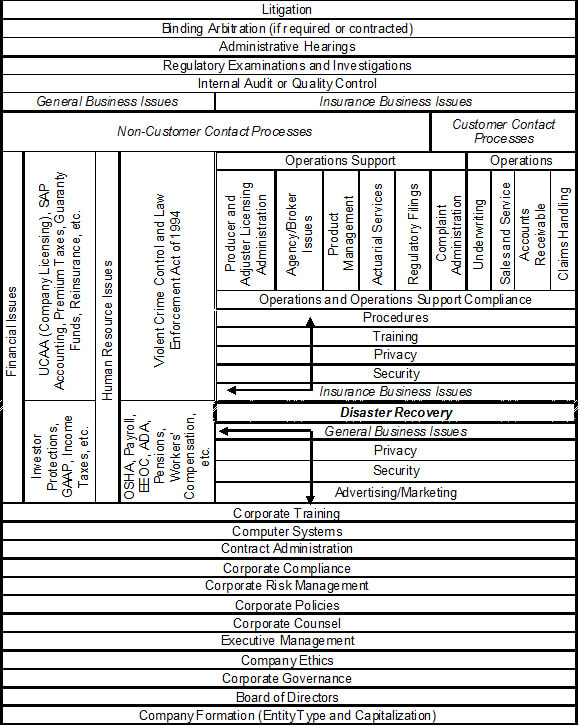

INTEGRATED VERTICAL AND HORIZONTAL PROCESSES. Horizontal processes drive the flow of work[16] and integrate vertical processes into a coherent system. Table 2 illustrates how an insurance company’s vertical and horizontal processes may be integrated and also displays the points of interaction between insurers and governmental authorities. As was done with vertical processes, the discussion is limited to compliance with laws specific to insurance companies. (The Appendix provides a discussion of the horizontal processes which are not specifically addressed by insurance laws.)

Table 2 – General Business and Insurance Business Processes

A corporation’s entity type and method of capitalization form the foundation of its processes. The requirements for an insurance company vary based on state insurance laws regarding formation as a stock company, mutual, reciprocal, etc., and whether capital funding is private or public. State insurance laws require that insurance companies have a board of directors and company officers. Company officers are responsible to develop and maintain business practices and procedures appropriate for the business.

To comply with new or changes to existing laws, an insurance company may need to alter its operations or operations support processes or periodically introduce new horizontal processes, such as privacy and security. In addition, training and procedures may need to be changed. Many states require insurance companies to develop plans for minimal disruption of service to its insureds in the event of a disaster. Disaster recovery laws are an example of an insurance law that applies not only to the operations processes but financial and HR processes as well. State insurance laws require companies to submit to regulatory examinations, with authority to require internal audits, and to participate in administrative hearings and arbitration.

How these vertical and horizontal processes interact is discussed next.

INTERACTION OF AN INSURANCE COMPANY’S PROCESSES

PARALLEL HORIZONTAL PROCESSES. The four major vertical processes of an insurance company – finance, human resources, operations, and operations support – are demonstrably different from each other, based distinctly upon the laws being complied with, the customers being supported, the different skills and aptitudes of employees, and the specialized professional certifications available to employees. However, recognizing horizontal processes as separate and distinct may not be as evident.

For example, although compliance and auditing are parallel processes, and there are laws requiring a company to conduct audits, the two processes are distinct. The compliance process focuses on the implementation of requirements from laws within the appropriate process or processes, while auditing focuses on the validation that these requirements were implemented properly, completely, and timely. Therefore, a compliance process reacts to new laws and proactively drives changes to the company’s other processes to assure there are no gaps in compliance. Conversely, auditing is a post-implementation process that proactively assesses the quality of the process being audited by validating whether processes are performing as expected and is reactive when non-compliance issues are uncovered. Only when those conducting an audit are not the same persons who assisted in the development of compliant processes are the audit results are objective and independently verifiable.[17]

Another example of parallel horizontal processes is compliance (with laws) and adherence (to contracts and policies). Governmental authorities establish laws and expect businesses to comply with those laws. A company signing a contract with another company expects the other company to fulfill its contractual obligations by complying with the terms of the contact. A company establishes its own policies and expects its employees to follow those policies consistently. It is expected that laws will be complied with and contracts and policies adhered to. With only the authority behind the requirements being different, the compliance and adherence processes are similar; however, even so, the scope of a compliance process is properly limited to requirements from laws.

INTERSECTING PROCESSES. To ensure the roles of a horizontal and vertical process that intersect remain separate, the interaction should be limited to the intersection point of the two processes. When the interaction is not limited, those outside of the intersecting processes many times see the roles of the intersecting processes as similar and indistinct. These examples will demonstrate the importance of establishing and maintaining separate roles for distinct processes.

Upon the identification of changes because of a new law or an amendment to an existing law, a compliance department is responsible to communicate those changes to the affected operations area. A compliance department would notify the claims department of a new law that affects claims handling. The claims department would then alter its processes as needed to comply. In so doing, the two departments focus on their respective specialties – compliance and claims – and the compliance department would not start performing work that properly belongs to the claims department.

In regards to customer complaints, the role of the compliance department is to identify new laws or changes to laws addressing complaint handling and ensure that a compliant process for responding to complaints is in place. Usually, either an operations support area or the operations area to which the complaint is addressed will respond to the complainant. A compliance department would not have line authority over operations staff and would not be able to administer corrective or disciplinary action to the employees whose actions have caused the complaint. Accordingly, the compliance department should not have responsibility for vertical processes such as responding to customer complaints.

Separate administration of all distinct processes focuses and limits the scope of responsibilities of all processes. When distinct processes are combined, the distinctiveness of each becomes blurred, from the perspective of those familiar and those unfamiliar with the processes. Blurred processes become inefficient and ultimately ineffective. The result of maintaining distinct processes as separate processes is the maximization of efficiencies and effectiveness.

Specialized skills, knowledge, aptitude, and, in some cases, a professional license or designation are needed required to effectively handle the flow of knowledge within the finance, HR, operations, and operations support activities. The availability of a professional certification or designation may be used as a straightforward method of distinguishing among processes. If a certification or designation is available for a specialized function, then that function and the process supported by it are distinct from other specialized functions and warrants administration as a separate process.

ADMINISTRATION OF THE COMPLIANCE PROCESS

Insurance companies have several options when determining which of the company’s departments will administer compliance. Many workable arrangements are possible that account for the complexities of general and insurance business laws, the multiple processes of any company, and the unique characteristics of individual companies. The structure below is an example that shows compliance both as a separate process and systemically embedded. In any configuration, hiring staff with the appropriate professional designations merits strong consideration.

- Dedicated staff supporting the specialized processes of finance, HR issues, and operations support are responsible for all of the compliance responsibilities associated with their specialized processes.

- An operations compliance manager supports all operations processes by identifying new compliance requirements for these operations. In this arrangement, the operations functions each concentrate fully on their core processes.

- A corporate compliance department supports the business having:

- Oversight of the compliance process for the entire company. To accomplish this, corporate compliance has authority with respect to compliance matters over the vertical processes of finance, HR, and operations, and operations support.

- Conducting the compliance process for laws that affect more than one horizontal process. This will ensure that the integration of these laws throughout all processes is generally consistent.

- Both the corporate compliance and auditing functions report to the Audit Committee of the Board of Directors. This will ensure board awareness and involvement in the separate parallel processes of compliance and auditing.

- The internal audit department, in addition to conducting audits to validate compliance, also audits for adherence to corporate policy. Additionally, based on the similar roles in post-compliance validation of audit and regulatory examinations, the internal audit department also supports regulatory examinations of the operations and operations support processes. The company that has only one source that drive changes required due to regulatory examinations and internal audits.

This configuration covers the height and breadth of compliance for insurance companies; including horizontal processes such as corporate policies and auditing, and vertical processes of finance, HR, and operations. The implementation of such an arrangement is one way to ensure that the company’s compliance process is holistic and systemic, which fosters fluency and comprehension between a company’s departments. With strong reporting relationships in place, the company’s board of directors is assured that the board’s corporate governance responsibilities regarding compliance are fulfilled.

SUMMARY

Every business is obligated to comply with a variety of laws from state and federal legislatures, regulatory agencies, and courts. Although states are the primary regulators of the business of insurance, some federal laws also affect the insurance industry, either directly or indirectly. Laws that affect insurers can be general, specific to an activity, or specific to certain types of insurance policies. To comply with changes to existing laws or new laws, companies must first be aware of the laws, regardless of the source, and then react to the laws. The processes companies follow in reaction to changes to laws are part of a compliance process, which proactively makes changes to business processes for the company to remain compliant.

All processes can be categorized as either vertical or horizontal. A vertical process drives the flow of knowledge while a horizontal process drives the flow of work. Horizontal processes are necessary to link all vertical processes into a coherent system. The effectiveness and efficiency of these links determines the effectiveness and efficiency of the business. The availability of a certification or designation for a specialized function is a sound indication that a vertical or horizontal process is distinct from other processes and should be maintained and administered as a separate process.

In the insurance industry, companies have many choices in determining the best method of administering the compliance process. A compliance process is often integrated within the finance, HR, and the various operations support processes. Operations processes may also have integrated compliance or a centralized compliance process may support operations. Each company’s compliance process should recognize both the company’s unique characteristics as well as the need the unique aspects of specialization within laws and the efforts taken to comply with specialized laws. When done, this ensures that the company specialists are fluent in and comprehend both the legal requirements and the company’s processes, resulting in harmony instead of confusion, fewer errors and cost savings. In turn, this provides assurance to the company’s directors that its corporate governance responsibilities regarding compliance are fulfilled.

APPENDIX

A. VERTICAL PROCESSES – GENERAL BUSINESS COMPLIANCE ISSUES

1. Finance Compliance[18]

- Treasury Management[19]

- External Financing

- Borrowing

- Leasing

- Investor relations

- Cash Management

- Collection

- Disbursements

- Short-term investing

- Investment Management

- Long term securities and equities

- Risk Management

- Employee Benefit Fund Management

- Controller

- SEC Oversight (limited to publicly traded companies) through the Securities Exchange Act

- Accounting

- Financial reporting

- Internal Accounting

- GAAP (Generally Accepted Accounting Principles)

- Auditing

- Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002 (some provisions apply to both public and private companies)

- Public Company Accounting Oversight Board (PCAOB) – auditing standards

- USA PATRIOT Act

- Tax reporting and tax filings (federal, state, local)

- Bank relationship management

- Payables – payroll (requires interaction with Human Resources), accounts payable

- Budget and Financial Planning

- Management Information Systems

- Credit and Accounts Receivable

- Electronic Funds Transfers

- ACH (Automated Clearing House) Coding

- External Auditor Relations

2. HR Compliance[20]

- Consumer Reports Used by Employers

- FCRA (Fair Credit Reporting Act, as amended by the FACT Act of 2003)

- Permissible use

- Disposal

- Adverse use

- Discrimination Protections

- ADA (Americans with Disabilities Act) and ADA Amendments Act of 2008

- ADEA (Age Discrimination in Employment Act of 1967)

- Civil Rights Act of 1964

- Civil Rights Act of 1991

- Equal Employment Opportunity Act

- EEOC’s E-RACE Program (Eradicating Racism And Colorism from Employment)

- Discrimination protections in connection with background checks

- The Employee Polygraph Protection Act of 1988 – employers may not request or require applicants or discipline employees for declining to take a polygraph test

- Family and Medical Leave Act

- Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act of 2008

- OWBPA (Older Workers Benefit Protection Act)

- Immigration Reform and Control Act of 1986 – employers may not discriminate against individuals based on national origin or citizenship

- Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002, Whistleblower Protection

- The Uniformed Services Employment and Reemployment Rights Act of 1994 (USERRA) – provides re-employment rights to military personnel and prohibits discrimination by employers

- Health Benefits/Retirement

- ERISA (The Employee Retirement Income Security Act of 1974)

- Family and Medical Leave Act

- Payroll Administration (requires interaction with Finance)

- Internal Revenue Act

- FLSA (Fair Labor Standards Act)

- Tax reporting

- Workplace Safety/Workplace Injuries

- OSHA (Occupational Safety & Health Administration)

- Workers’ Compensation Insurance

- Release of Employees – Mass Layoff

- Worker Adjustment and Retraining Notification (WARN) Act

- Employability Standards

- Immigration Reform and Control Act of 1986 – only persons who are able to prove they are authorized to work in the United States may be hired by an employer

3. General Business Compliance Issues

- Advertising/Marketing

- Telemarketing Sales Rules (”Do Not Call”) issued by the Federal Trade Commission or similar rules issued by a comparable state agency to protect the public from unwanted telemarketing

- Intellectual Property

- Patent, Copyright, Trademark, Servicemark, Patent and Trade Secret protections

- Obtaining, Using, and Protecting Information

- Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act

- HIPAA (Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996)

- Products/Services Sold to Members of the U.S. Military

- SCRA (The Servicemembers Civil Relief Act of 2003) and related state laws

- Conducting Business Electronically

- UETA (Uniform Electronic Transactions Act)

- E-Sign (Electronic Signatures in Global and National Commerce)

- Document Retention (Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002)

B. HORIZONTAL PROCESSES – GENERAL BUSINESS COMPLIANCE ISSUES

1. Corporate Governance Issues

The Sarbanes-Oxley Act requires publicly traded companies to have a corporate governance plan. The New York Stock Exchange requires every company listed by the Exchange to have “certain standards regarding corporate governance,” regarding “corporate responsibility, integrity and accountability to shareholders.”[21] Companies not listed by the Exchange may opt to develop corporate governance policies based on the Exchange’s standards to be modernistic, before going public, or because a lender requires it.

2. Establishment of Various Corporate Policies and Departments

A board establishes an ethics policy to provide general oversight and direction for corporate behavior. Corporate counsel serves as consultants for the company’s board and management with the development of corporate policies. In addition to supporting policy formation, corporate counsel should be involved in nearly every aspect of the company’s processes, particularly all issues regarding laws and contracts. Risk management is sometimes set up as a separate department with responsibility to identify and reduce exposure to all types of risks to the company. A corporate compliance department may be established and have responsibility to administer the overall compliance process. Counsel’s legal interpretation of risks and laws is supportive of the risk management and compliance processes.

A company’s ethics policy, or code of business conduct, often states that the company will comply with all known laws. (The three largest P&C insurers in the United States from the 2011 Fortune 500 list[22] make a similar statement,[23] and others very likely do as well.)

Many companies form departments to administer contracts the company signs. In support of risk management, the contract department should validate that all employees adhere to corporate policies in areas such as contractual data-sharing agreements. A corporate training department may be formed. Policies to address the topics of security of its employees, customers, premises, systems, and intellectual property may be established. A corporate audit or internal audit department would be formed in part to validate that the company’s various processes are compliant with laws and adhere to corporate policies. The company would also establish departments for computer processing and advertising and marketing.

REFERENCES

American International Group, “Code of Conduct” [http://www.aigcorporate.com/corpgovernance/code_of_Conduct2010/AIGCodeOfConductEng.pdf].

Berkshire Hathaway Group, “Berkshire Hathaway Inc. – Code of Business Conduct and Ethics.” [http://www.berkshirehathaway.com/govern/ethics.pdf].

CNN/Money Homepage, Fortune Magazine, “Fortune 500 2011” Rankings by “Industry: Insurance: P & C (stock)”, [http://money.cnn.com/magazines/fortune/fortune500/2011/industries/182/index.html] and (mutual) [http://money.cnn.com/magazines/fortune/fortune500/2011/industries/184/index.html].

Cornell University Law School, LII/Legal Information Institute, “UCC: uniform commercial code”, [http://www.law.cornell.edu/ucc/1/].

Corporate Legal Times, “The Roundtable Sponsored by Littler Mendelson: Compliance Matters – What Should You Be Doing to Build Better Compliance Policies?”, September 2005:1, [http://www.insidecounsel.com/pdfs/SeptRoundtable.pdf]

Department of Health and Human Services, “Mandatory Insurer Reporting: Liability Insurance, Self-Insurance, No-Fault Insurance and Workers Compensation”, [http://www.cms.hhs.gov/MandatoryInsRep/03_Liability_Self_No_Fault_Insurance_and_Workers_Compensation.asp#TopOfPage].

The Institute of Internal Auditors, “International Standards for the Professional Practice of Internal Auditing”, [http://www.theiia.org/guidance/standards-and-guidance/ippf/standards/full-standards].

National Association of Insurance Commissioners, NAIC/AICPA Working Group, Financial Condition (E) Committee, “Model Audit Rule Revisions”, [http://www.naic.org/committees_e_naic_aicpa_wg.htm].

National Association of Insurance Commissioners, News Release “Insurance Regulators Adopt Climate Change Risk Disclosure”, [http://www.naic.org/Releases/2009_docs/climate_change_risk_disclosure_adopted.htm].

National Association of Insurance Commissioners, “Climate Change and Global Warming (EX) Task Force 2010 Fall National Meeting, Sunday, October 17, 2010, 5:00 – 6:00 p.m. Handout”. [http://www.naic.org/documents/committees_ex_climate_101017_handout.pdf]

National Capital Language Resource Center (NCLRC). “The Essentials of Language Teaching, Goal: Communicative Competence”, [http://www.nclrc.org/essentials/goalsmethods/goal.htm].

New York State Insurance Department, “Circular Letter No. 11 (2009),” “Compliance with the Federal Bank Secrecy Act, Foreign Corrupt Practices Act, and Office of Foreign Assets Control Requirements”, [http://www.ins.state.ny.us/circltr/2009/cl2009_11.htm].

New York Stock Exchange, “Final NYSE Corporate Governance Rules”, [http://www.nyse.com/pdfs/finalcorpgovrules.pdf].

New York Stock Exchange, “Listed Company Manual”, Section 301.00 Introduction, [http://www.nyse.com/Frameset.html?displayPage=/listed/1022221393251.html].

Securities and Exchange Commission. Final Rule: Revision of the Commission’s Auditor Independence Requirements, [http://www.sec.gov/rules/final/33-7919.htm].

Snider, Keith F., and Nissen, Mark E., “Beyond the Body of Knowledge: A Knowledge-Flow Approach to Project Management Theory and Practice”, Project Management Journal, June 2003: 6.

State Farm Insurance Companies, “State Farm® Code of Conduct 2011“. [http://www.statefarm.com/_pdf/2011-code-of-conduct.pdf

United States Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics, “Occupational Outlook Handbook, 2010-11 Edition,” “Financial Managers”, [http://www.bls.gov/oco/ocos010.htm].

United States Senate Committee on Banking, Housing, & Urban Affairs, “Brief Summary of the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act”. [http://banking.senate.gov/public/_files/070110_Dodd_Frank_Wall_Street_Reform_comprehensive_summary_Final.pdf].

United States Department of the Treasury, “Civil Penalties Information Chart”. “Enforcement Information for June 3, 2010”, [http://www.treasury.gov/resource-center/sanctions/OFAC-Enforcement/Pages/20100603_33.aspx] and “Enforcement Information for April 7, 2011”, [http://www.treasury.gov/resource-center/sanctions/CivPen/Documents/04072011.pdf].

United States Treasury, “Home/Resource Center/FAQs/Sanctions/Frequently Asked Questions and Answers.” [http://www.treasury.gov/resource-center/faqs/Sanctions/Pages/answer.aspx].

United States Treasury, Office of Foreign Assets Control, “Foreign Assets Control Regulations and the Insurance Industry”, April 29, 2004: 1, [http://www.ustreas.gov/offices/enforcement/ofac/regulations/t11facin.pdf].

United Stated Department of the Treasury, “Terrorism Sanctions: What is Your OFAC Risk”, [http://www.treas.gov/offices/enforcement/ofac/programs/terror/terror.shtml].

ENDNOTES

Endnotes 5, 6, and 7: United States Department of the Treasury, “Civil Penalties Information Chart”. Endnotes 4 and 6: “Enforcement Information for April 7, 2011”, [http://www.treasury.gov/resource-center/sanctions/CivPen/Documents/04072011.pdf]; Endnote 5: “Enforcement Information for June 3, 2010”, [http://www.treasury.gov/resource-center/sanctions/OFAC-Enforcement/Pages/20100603_33.aspx], sites accessed April 12, 2011.

2. American International Group, “Code of Conduct” [http://www.aigcorporate.com/corpgovernance/code_of_Conduct2010/AIGCodeOfConductEng.pdf], site accessed May 10, 2011.

3. State Farm Insurance Companies, “State Farm® Code of Conduct 2011“. [http://www.statefarm.com/_pdf/2011-code-of-conduct.pdf], site accessed May 10, 2011.

Joseph L. Wiest, CPCU, ARC, ACP, is a corporate compliance director of market conduct with a top ten P&C insurance group. He is a graduate of the University of Nebraska, having earned a B.S. in business administration. Since 1984, he has been employed in the insurance industry, working 20 years for a major personal lines direct writer, holding positions in customer service, line underwriting, staff underwriting, and compliance. He also served as the compliance officer of a nonstandard auto carrier for two years. He has earned a business ethics certificate from Colorado State University in addition to nine other professional insurance designations.